Bonds were seen as a safe haven – but they are central to this bank crisis

I f you’re a banker, it’s been a month to forget. Two regional US banks have gone to the wall, central banks on both sides of the Atlantic have been forced to provide hundreds of billions of dollars in emergency lending to shore up the financial system, and the Swiss financial group Credit Suisse has been ignominiously absorbed into the larger UBS at the behest of its regulator. About half a trillion dollars have been wiped from banks’ stock market valuations.

Although history doesn’t repeat itself, it rhymes sufficiently to ask whether we are on the brink of anther global financial crisis. A bit of context for the current troubles might help answer.

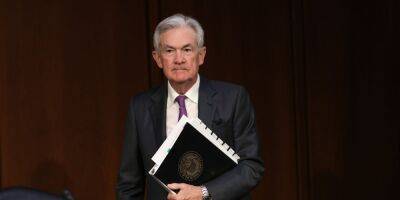

Inflation is high in the UK, mainland Europe and the US. The standard macroeconomic policy to arrest high inflation is not to strike hard public sector pay deals; it is for central banks to increase interest rates. Higher rates mean a higher cost of borrowing for everyone, reducing the propensity of households and businesses to spend money on credit and reducing aggregate demand versus supply. Doing this in a way that cools inflation without inducing a recession is a hard balance to strike. This is precisely what the Bank of England, European Central Bank and the US Federal Reserve have been trying to do for the past year.

Increasingly, these interest rate increases are causing problems to pop up in different parts of the global financial system. And the common thread running through this and other recent crises is the bond market, composed of IOUs issued by governments and companies alike.

While Kwasi Kwarteng’s mini-budget was the spark that ignited the financial maelstrom in the UK last autumn, rising interest rates and sinking bond prices in the months leading up to that

Read more on theguardian.com

![Shiba Inu’s [SHIB] slump may continue despite increased demand: Here’s why](https://finance-news.co/storage/thumbs_400/img/2023/3/24/61335_vep.jpg)