‘I’m gonna have to make my own money’: the rise of the side hustle

In 2010, not long into my first job on a magazine now in the great magazine graveyard in the sky, a fellow junior and I were appraising the performance of a new intern. Fresh out of university, this person had arrived late and then suggested they conduct the celebrity interview for the next issue. “That’s the thing with these young ones coming through now,” my colleague said with a solemn shake of their head, “they just don’t want to put the graft in.”

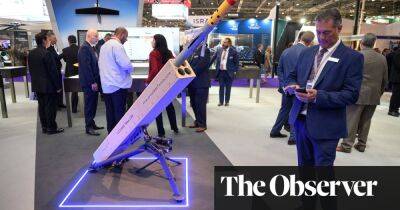

Twelve years later and society is in a moment of transformation when it comes to work and our attitudes towards it. The Great Resignation – or at least the Great Thinking About Resignation – is upon us. The Covid pandemic smashed through many of the grand narratives we have passed down for generations about having a job: the need to be present in an office, the idea we are somehow indispensable to the wider machine we are operating in.

For older people already in charge, this meant scrambling to adjust the modern workplace to be more flexible and inclusive in the hope this would keep the young people in their organisations happy. But Generation Z already had other ideas. It’s not just that many of them entered the workplace in the era of Covid. It’s that they had already watched my generation – the pitiful Millennials – get sucked into a broken social contract, the one that promised if you found a good job and worked hard, you’d get ahead. They saw us stifled and infantilised by two recessions, mired in existential despair about the housing crisis and now vulnerable again as the cost of living crisis asserts its grip.

Gen Z stand up to their employers in a way no previous generation has, something usually dismissed as a spoiled sense of entitlement. But in record numbers,

Read more on theguardian.com