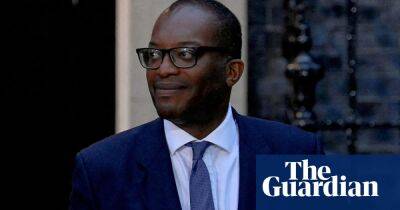

Kwarteng’s fiscal pyrotechnics caused this mess – now we need some U-turns

The good news is that there are still officials at the heart of UK decision-making who can recognise a financial crisis when it is staring them in the face. That’s not saying much, admittedly, but at least the Bank of England, having fiddled nervously all week, has emerged from its bunker. It will buy long-dated government gilts to quell the riot in the market that is most crucial in setting the long-term cost of borrowing in the economy.

The bad news is that the Bank’s hand was forced by the real danger of a calamity. Threadneedle Street does not use the phrase “a material risk to financial stability” lightly. Dysfunction was feeding on itself. Pension schemes were becoming forced sellers of gilts to top up their short-term capital buffers. They could not handle the spectacular blow-out in yields since Kwasi Kwarteng’s mini-budget last Friday. In a market where a daily move of a tenth of a percentage point is normally noteworthy, the yield on 30-year gilts had blown out from 3.6% to 5.1%. Yes, the Bank definitely had to act.

It is at this point, one hopes, that reality dawns on Tory MPs that the current crisis has very little to do with a strong dollar or global forces, or any of the other excuses that have been trotted out in recent days. The Bank had to intervene to save the government from the consequences of its own actions.

While forced selling by pension funds intensified the action, the deeper turmoil comes by markets’ brutal verdict on Liz Truss and Kwarteng’s £45bn package of tax cuts. It was investors – not the International Monetary Fund, say – who first judged that the chancellor’s plan is no way to manage the public finances when you are borrowing potentially huge sums to underwrite a blank-cheque guarantee on

Read more on theguardian.com